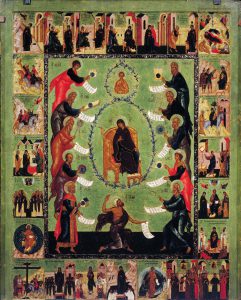

The Laudations of Our Lady of the Akathist, 16th Century Icon

Source: OINOSConsulting.com

Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here and Part 3 here.

by Frank Marangos D.Min., Ed.D.

“Happy is that house which is visited by some royal personage. But more happy is the soul that is visited by the Queen of the world, the most holy Mary, who cannot but fill with mercies and graces those blessed souls whom she deigns to visit with her favors.” ~ Saint Alphonsus de’ Liguori

In 626, while the Byzantine Emperor Heracleios was on a military expedition, a barbaric horde laid siege upon his territory’s defenseless capital. In desperation, the outnumbered citizens of Constantinople turned to Patriarch Sergius for spiritual intercession. With an Icon of the Holy Mother (Theotokos) in hand, the ecumenical leader of the Christian Church (610 to 638) bolstered the confidence of the panic-stricken inhabitants by leading a procession of clergy around the city’s great walls. Historians indicate that, as result of this Joshua-styled supplicatory expression (Joshua 6:1-27), a divinely initiated storm suddenly appeared over the harbor. With most of their fleet devastated by enormous tidal waves that accompanied the tempest, the horrified enemy was forced to retreat and the city was saved.

From its inception, the city of Constantinople was closely allied to the protection of the Virgin Mary. Numerous Christian hymns and historical texts can be cited that refer to the then capital of the Byzantine Empire as the “Queen’s City.” The Holy Mother’s supplications on behalf of her metropolis supported an emotive surety similar to that provided to the citizens of Jerusalem by the Ark of the Covenant. In fact, as a result of the aforementioned miracle attributed to her maternal mediation, the Akathist Hymn, the 6th century Christian poem dedicated to the virtues of Mary, has often been chanted to honor her personage as the “Spiritual Ark of God.”

As discussed in the three previous commentaries of Frankly Speaking, the 24-stanzas of the Akathist Hymn provide a valuable four-part paradigm for the discovery and use of executive voice: (a) vocation, (b) validation, (c) valuation, and (d) veneration. While the 1st Section (Stanzas 1-6) of the Akathist Hymn was used to focus on the Holy Mother’s acceptance of the Holy Spirit’s vocare, the subsequent Section (Stanzas 7-12) of the ancient canticle poetically illustrated how the Virgin’s acquiescence, was validated by her faithful vocational witness. As observed in the preceding commentary, the 3rd Section (Stanzas 13-18) of the Akathist Hymn focuses on the valuation of the Incarnation. In this final commentary, the 4thSection of the Akathist Hymn (Stanzas 19-24) will be used to examine the topic of prayer.

According to the Old Testament, worship and prayer are closely related to the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark was a sacred religious box, 4 feet long, 2 feet wide, and 2 feet deep, made from acacia wood, plated with gold, and crowned with an atonement cover or “mercy seat,” flanked by two angels. It contained (a) the two stone tablets of the Law given to Moses by God on Mt. Sinai, (b) a jar of Manna that sustained the Israelites during their wilderness journey to the Promised Land, and (c) the rod of Aaron that miraculously budded, and thereby, validated his priestly leadership (Heb. 9:4; Num.17:10; Ex. 16:32-34). The atonement cover designated God’s throne where, “between two angels,” Yahweh promised to “meet” and “guide” the spiritual and civic leadership of Moses (Exodus 25:22).

Epitomizing the presence, power, and agency of God, the Ark of the Covenant was the most important religious object for the Judaic nation. After their miraculous Exodus from Egypt, the Israelites carried and continually re-located the Ark in a specialized tent during their subsequent 40-year desert sojourn. After the conquest of Canaan, the Ark was brought to Jerusalem where David’s son and successor, King Solomon, built a Temple to permanently house and faithfully venerate it. According to the Old Testament, the Ark signified the awesome sovereignty of the invisible God whose inaccessibility was due to original sin. As sudden death could therefore result from undeservedly looking at it, the Ark was placed within the sanctuary’s “Holy of Holies,” only visible to the Jewish High Priest once a year (Leviticus 16:2).

Due to the inherent dangers associated with its inviolability, the Old Testament provides detailed instructions to leaders about the handling and reverence of the Ark. While the disobedient and careless would be severely punished, those who treated the Ark with reverence were promised God’s blessings. An example of appropriate faithfulness is best illustrated in the life of Obed-Edom (2 Samuel 6; 1 Chronicles 13). While rabbinical literature refers to “Obed” as a “servant who honors God in the right way,” the Bible describes him as a “faithful leader of Israel” who graciously stored the Ark in his own house for three months. Typologically foreshadowing what would later become the 3-month visit of the Theotokos to the house of Elizabeth, the Ark’s 3-month “sojourn” in the house of Obed-Edom resulted in a “blessing to him and to his entire household” (2 Samuel 6:12).

Unfortunately, due to inattention and neglect of what the Ark represented, the nation’s spiritual life gradually declined (1 Samuel 13:13; 15:11). Over time, the adoration of the Almighty presence diminished to the point that King Saul sought spiritual as well as civic guidance from a witch instead of God (1 Samuel 28). Finally, as a result of Yahweh’s displeasure with His chosen people’s faithlessness, the glory, counsel, and protection of God was allowed to depart from Israel when, after the sack of the Jerusalem Temple in 586 B.C., the Sacred Ark disappeared (1 Samuel 4-6). The focus of folklore and numerous mysterious tales, the existence and/or current resting place of this central Old Testament symbol of God’s presence on earth, remains a topic of speculation and debate to this day.

What does the Ark of the Covenant have to do with the vitality of leadership? Should prayer, understood as adoration, veneration, supplication, and intercession, be a foundational priority of a contemporary leader’s professional as well as personal sensibilities? And what, if anything, does the Mother of God have to do with this spiritual dimension of leadership?

The Akathist Hymn advocates that as Theotokos (God-Giver), the Holy Mother of Jesus, is the “Sacred Ark” of the New Covenant that tenders the Word (Commandments), Provision (Manna), and Guidance of God (Aaron’s Rod), to those who prayerfully acknowledge His Sovereignty through: (a) adoration, (b) veneration, (c) supplication, and (d) intercession. Unfortunately, due to the inherent hazard of reinforcing the faulty “God-in-a-box” notion that Christ is the cosmic porter, ever ready to respond to humanity’s self-centered bell ringing, the schema of such a comprehensive understanding of prayer and its association to leadership has not been adequately examined.

The life of the Mary is shrouded in deep mystery. According to a tradition, preserved and celebrated by the Christian Churches of the East and West, the Virgin Mary was born in a cave near the Bethesda Pool where her Son Jesus would one day perform miracles. When she reached the age of three, her parents, Saints Joachim and Anna, dedicate her to the service of God. Satisfying the vow that if a child was born to them they would commit it to God, young Mary was escorted into the Temple where, in fulfillment of the prophetical message of Psalm 45, she inexplicably entered the Holy of Holies by her own accord. Astonished at this most unusual occurrence, the chief rabbi permitted the young girl to remain in the Ark’s physical location, where her formative years were spent in the diligent reading of Scripture and constant prayer.

Regarded by the Orthodox Christian Church as one of the 12 Great Feasts of the liturgical year, a special festival was established in honor of the Most Holy Mother’s’ Entry into the Temple in the first century. A most inspiring hymn of the festal celebration underscores Mary as the Living Ark of God. “Today,” insists the canticle, “the parents of Mary with joy bring to the temple of the Lord the True Temple and pure Mother of God. Today the universe is filled with joy and cries out. She is the heavenly tabernacle.”

The Akathist Hymn uses a variety of titles to compare the Blessed Virgin to the Ark of the Covenant. The Canticle refers to her as “Tabernacle of God,” “Gilded Ark of Holy Spirit,” “King’s Throne,” “Abode,” “Vessel of God’s Wisdom,” and “Treasury.” Whatever title is used, her incarnational vocation is validated in terms of “offering God the Logos” to the Church.

According to the Akathist Hymn, Mary is the model, icon, and theological cipher of the New Ark. Just as God’s glory “overshadowed” the Ark of the Jerusalem Temple, so too does it now “overshadow” Mary, the Ark of the New Covenant. While the Ark of the Old Covenant pre-figured the presence of God, Mary, on the other hand, actually contained within her the Incarnate God become Man. As such, apart from being the archetype of Virginity and Mother, she is also the exemplar of the intercessor that cares deeply for the wellbeing of others. She is the spiritual teacher of prayer whose paradigmatic act of affirming the Archangel’s invitation re-defines leadership as an act of sacrificial service.

The Akathist Hymn re-associates the three articles placed in the interior of the Ark to the Incarnate Child in Mary’s womb. While the symbol of Old Testament Manna is redefined in terms of Christ’s sacramental provision of His Body, the “Wood of the Cross” replaces the Ark’s Rod of Aaron. Since Jesus “is the first-fruits from the dead” (1 Corinthians15:20), the Resurrection is now recognized as the blossom that replaces the budding rod of Old Testament leadership. Finally, the Law, represented by the stone tablets of the Decalogue, is replaced by the Grace of the living Christ, the Pre-eternal Word (Logos) of God.

During her formative years in the Holy of Holies, Mary assuredly learned the value and various forms of prayer. While venerating the Ark’s contents, she experienced the power of adoration – the worship of One True God, who invisibly reigned from the Tabernacle’s Mercy Seat. In adulthood, Mary’s prayer life developed to also include supplication and intercession. Finally, having humbly acquiesced to become the Mystical Temple of the Holy Spirit, Mary becomes both exemplar and agent of authentic prayer.

The Akathist Hymn honors the Mother of Jesus as the Living Ark that humbly acknowledged, valued, and attested to the divine sovereignty of Her Son and Savior. In the end, her headship in the Church is based on her maternal participation in the Incarnation that liberated the presence of God from the custodial confinement of a sacred box hidden in a temporal refuge. By reason of His Mother’s vocational acquiescence, the Veil of the Jerusalem Sanctuary was torn in two, and the Word, Provision, and Sovereignty of God became accessible to all.

The following matrix links the components of the Old Testament Ark of the Covenant with the vocational identity of the Theotokos. Apart from providing a brief description of each form of prayer, the template outlines a framework that leaders can use to evaluate the degree to which prayer reinforces their respective areas of executive voice.

Numerous research projects have been conducted to evaluate America’s attitude to prayer. A Barna Research project (2011), for example, reports that slightly more than 84% of adults in the United States claim they had prayed in the past week. A U.S. News Report (2004) indicates that, while 64% of respondents pray more than once a day, only 3.3% admit that they pray for individuals outside their immediate family. Remarkably, only 1.5% specified that their prayers were never answered. Finally, a 2014 Gallup Poll reports that 76% of Americans favor “a constitutional amendment to allow voluntary prayer in public schools,” while just 23% oppose such an amendment. Only 23% of Americans prefer some type of spoken prayer, while 69% favor a moment of silence for contemplation or silent prayer.

In support of the aforementioned data, numerous successful executives have fortuitously indicated the importance of integrating prayer into their respective administrative contexts. A partial list of such CEOs includes, Donnie Smith (Tyson Foods), Indra Nooyi (PepsiCo), James Tisch (Loews Corporation), Arne M. Sorenson (Marriott International), Bryan Bedford, (Republic Airways), Daniel P. Amos (Aflac), and Jeffrey B. Swartz (Timberland Shoes). When interviewed, these leaders have indicated they use prayer at work for guidance in decision-making, to prepare for difficult situations, to overcome difficulties, and/or to express gratitude for success.

In their noteworthy book, Spiritual Leadership(2011), Henry and Richard Blackaby outline six reasons why leaders should develop and continually refine their regular discipline of prayer. According to the authors, prayer (a) is an essential leadership activity, (b) provides the guidance of the Holy Spirit, (c) imparts God’s wisdom, (d) provides accesses to God’s power, (e) relieves stress, and (f) reveals God’s agenda.

Like the Blackabys, Rosabeth Moss Kanter, professor at Harvard Business School, suggests that the connections among prayer, work, and service to others “are ripe for reinvention.” Noting the emergence of “values-based capitalism,” Kanter commends three particular principles for the renewal of the faltering American enterprise: (a) open minds of creativity, (b) search for higher purpose and sense of meaning, and (c) inclusiveness and shared responsibility. In her December 2010 Harvard Business Review column, Kanter emphasized the value of identifying higher purpose and meaning, and recommended that leaders put spirituality “on top of the their management agendas.”

Apart from it value to individual leaders, prayer may also distinguish organizational culture. In their book, A Spiritual Audit of Corporate America(1999), Ian I. Mitroff and Elizabeth Denton report, “that spirituality is one of the most important determinants of organizational performance in America.” In fact, the authors insist that, “spirituality may well be the ultimate competitive advantage.” Their research presents the following five models of “spiritual organizations” existing in America today.

- Religion-Based Organization brings religion into the workplace in overt ways and is usually directly affiliated with an organized religion.

- Evolutionary Organization initially has a strong association or identification with a particular religion and, over time, evolves to a more ecumenical position.

- Recovering Organization adopts the principles of Alcoholics Anonymous as a way of fostering spirituality.

- Socially-Responsible Organization guided by strong spiritual principles for the betterment of society.

- Values-Based Organization is guided by general philosophical principles or values of its founders that are not aligned or associated with a particular religion or even with spirituality.

Finally, according to Bill George, Kanter’s Business School colleague and former CEO of Medtronic, “the biggest derailleur of executive leadership is not lack of IQ or intensity, but the challenges they face in staying focused and healthy. According to George, “authentic leaders are genuine, moral and character-based leaders. They are people of the highest integrity, committed to building enduring organizations … who have a deep sense of purpose and are true to their core values, who have the courage to build their companies to meet the needs of all their stakeholders, and who recognize the importance of their service to society.” To be equipped for the rapid-fire intensity of executive life,” suggests George, “executives should cultivate the daily practice of prayer, among other disciplines that will allow them to regularly renew their minds, bodies, and spirits.”

Unsurprisingly, long before executives and business scholars discovered its importance, Christian writers throughout history have stressed the importance of prayer for those in authority. However, unlike the vague spirituality described by contemporary leadership experts, they stressed a more distinctive approach to prayer that included the veneration of the Mother of God.

In his exposition on the Book of Proverbs, Saint Ignatius, the 1st Century Martyr, identified the Theotokos as the “Wisdom” that King Solomon describes as having “built herself a house” (Proverbs 9:1). Mary is “this House of God,” insists Ignatius, “which God himself built on this earth for his habitation.” Saint John of Damascus, a 4th Century ecclesiastical leader, similarly refers to Mary as the “fenced city of refuge” wherein sinners and faithful alike find a home of protection and forgiveness. Finally, like Ignatius and John, Saint Augustine, the 4th Century philosopher and Christian theologian, insistes that the Son of God “built himself no house more worthy than Mary, who was never taken by the enemy, nor robbed of her ornaments.”

According to Saint Gregory Palamas, the 14thCentury Archbishop of Thessalonica, in order to “refashion” humanity, God chose an appropriate handmaiden “renowned for piety and understanding,” as “His divinely fitted chariot.” Therefore, “like a Treasure of God,” writers Gregory, “Mary was stored in the Holy of Holies, so that in due time, she would serve for the enrichment of, and an ornament for, all the world.” “Let us turn our reason and our attention from earthly concerns,” counsels Saint Gregory, “and raise them to the inaccessible places of Heaven, to the Holy of Holies, where the Mother of God now resides.”

Aside from the more ancient Christian writers, Saint Alphonsus de’ Liguori, the 18th Century Italian Catholic bishop, composer, and founder of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (Redemptorists) wrote extensively about Mary’s on-going participation in God’s relationship with humanity. In addition to other theological and ascetic works, this widely read Catholic spiritual author is best known for his spiritual reflection entitled, The Glories of Mary, that present a theological defense of the Blessed Virgin’s divinely appointed identity and vocational merits.

Saint Alphonsus straightforwardly validates the vocational identity of Mary. “I salute you,” prays Alphonsus, “as the Temple of God’s Glory, and the Sacred House of the King of Heaven.” He contends that when she was created, the Lord instructed her “to feed His lambs.” As such, “whoever bears the seal of being a servant of Mary,” insists Alphonsus, “has their name already written in the book of life.” Finally, Alphonsus extols his devotion to the Theotokos by stating that, like Obed-Edom, any house visited by the Mother of God is truly blessed. “But unlike Obed-Edom,” he contends, “much greater blessings enrich those who receive some loving visit from the Blessed Mother – the Living Ark of God!”

Contemporary leaders would do well to emulate the reverence and obedience of Obed-Edom, whose passion for the appropriate reverence of the Ark, was a vital key for stewarding his influence. Humanity’s access to God’s presence is a precious privilege made possible by the vocational assent of the Theotokos. Like Obed-Edom, when leaders make the sovereignty of God a priority in their personal as well as professional lives, they benefit from His word, provision, and guidance. Unfortunately, to a society that unreservedly celebrates positions of power, prestige, and performance, prayer – understood as adoration, veneration, supplication, and intercession – appears anachronistic.

The “sacred box” in most modern homes is the computer. As fixtures, judgments, and affections are often centered on its digital dispatches, this contemporary “ark” has the power to uncritically define values, influence relationships and shape worldviews. Unlike this secular chest, the central focus of Obed-Edom’s house was the Ark of God, whose sacred essentials reminded his family of God’s commandments, provision, and sovereignty.

According to the Catholic writer, Thomas Merton, “cowardice keeps us double minded, hesitating between the world and God. In this hesitation,” continues the Trappist monk, “there is no true faith. Faith remains an opinion, because we never quite give in to the authority of an invisible God. And this hesitation makes true prayer impossible.”

Like Obed-Edom, contemporary leaders should commit to courageously hosting the Ark of God within their homes, minds, and respective administrative contexts. In addition, like Noah, who “in holy fear built an ark to save his family from the flood” (Hebrews 11:7), authentic leaders should focus on the wellbeing of their followers and constituents by single-mindedly following a similar design. Finally, like the Theotokos, contemporary leaders must unhesitantly accept the invitation to more effectively serve society by shaping a sturdy ark of prayer in their personal as well as professional lives. Only in this fashion can values, relationships and worldviews bend their knee to the sovereignty of God.

Figuratively sent to their knees like the vulnerable inhabitants of the Byzantine capital city of Constantinople by global political, economic, and cultural assaults, contemporary executives have nowhere else to go but to respectfully open the doors of the Living Ark. There, within the closet of prayer, they will begin to hear the Voice that will sustain the resonance of their vocational aspirations. Humanity would be most fortunate to have such leaders living in its midst, as it will most certainly continue to receive the furtive subsidy of their Divinely inspired influence.