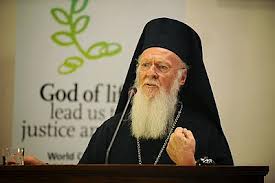

Source: Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

(October 13-14, 2012)

It is a sincere privilege to be invited by the Prime Ministry Office of Public Diplomacy and the SETA Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research to address this 1st Istanbul World Forum held under the distinguished auspices of and officially opened by His Excellency Prime Minister Erdogan. Moreover, it is a personal pleasure to participate in this esteemed panel on the critical subject of “Religion and Social Justice.”

The world of faith can certainly prove a powerful ally in efforts to address issues of social justice. For religion provides a unique perspective – beyond the merely social, political, or economic – on the need to eradicate poverty, to provide a balance in a world of globalization, to combat fundamentalism and racism, as well as to develop religious tolerance in a world of conflict. It is precisely the role of religion to respond to the needs of the world’s poor as well as to the world’s most vulnerable and marginalized people.

In fact, it is a rare instance where a faith institution is not a defining marker of the space and character of a community. Religion is, therefore, arguably the most pervasive and powerful force on earth. This is why it comes as no surprise to us that religion and the faith communities are proving to be the subject of renewed interest and attention in international relations and global politics, directly affecting social values and indirectly impacting state policies.

After all, not only does religion play a pivotal role in people’s personal lives throughout the world, but religions play a critical role as forces of social and institutional mobilization on a variety of levels. While the theological language of religion and spirituality may differ from the technical vocabulary of economics and politics, nevertheless the barriers that at first glance appear to separate religious concerns (such as salvation and spirituality) from pragmatic interests (such as commerce and trade) are not impenetrable. Indeed, such barriers crumble before the manifold challenges of social justice and globalization.

If we are honest to God, then we cannot overlook the calamitous impact of the economic crisis and social predicament that plague our world. If we are honest with ourselves, then we cannot ignore the victims of poverty and injustice that are no longer in the faraway distance but in fact in our very midst. They are quite literally, as Jesus Christ described them two thousand years ago, our brothers and sisters, whom he identified with the very person of God!

Thus, whether we are dealing with environment or peace, poverty or hunger, education or healthcare, there is today a heightened sense of common concern and common responsibility, which is felt with particular acuteness by people of faith as well as by those whose outlook is expressly secular. Such growing signs of a common commitment to work together for the well-being of humanity and the life of the world are encouraging. It is an encounter of individuals and institutions that bodes well for our world. And it is involvement that highlights the supreme purpose and calling of humanity to transcend political or religious differences in order to transform the entire world for the glory of God.

In recent years, we have learned some important lessons about caring for the natural environment. However, we have also learned that environmental action cannot be separated from human relations. What we do for the earth is intimately related to what we do for people – whether in the context of human rights, international politics, poverty and social justice or world peace. It has become clearer to us that the way we respond to the natural environment is directly related to and reflected in the way we treat human beings. This is precisely why, in the fourth century, St. John Chrysostom underlined the universal application of the Lord’s Prayer. Indeed, by praying to “our Father in heaven,” we also embrace a universal – even global – vision of the world. For, Christ asked us to implore: “Your kingdom come; Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” (Matt. 6.10) Chrysostom points out that Christ does not say “Your will be done in me or even in us, but “everywhere on earth.”

Nevertheless, at the same time, we have to admit that, while we have become more sensitive to environmental issues, we continue to ignore some fundamental issues of human welfare. This surely amounts to an unbearable contradiction. The world is a gift from God, and it is offered to us for the purpose of sharing. It does not exist for us to appropriate selfishly, but rather to preserve humbly. The way that we relate to God (in heaven) cannot be separated either from the way we treat other human beings or from our treatment of the natural environment (on earth). To disconnect the two would amount to nothing less than hypocrisy.

In our efforts, then, for the preservation of the natural environment, we must ask ourselves some difficult questions about our concern for other human beings and about our way of life and daily habits. Just how prepared we are to sacrifice our excessive lifestyles in order for others to enjoy the basic right to survive? What are we prepared to surrender in order to learn to share? When will we learn to say: “Enough!”? How can we direct our focus away from what we want to what the world and our neighbor need? Do we do all that we can to leave as light a footprint as possible on this planet for the sake of those who share it with us and for the sake of future generations? If we do not choose to care, then we are not indifferent onlookers; we are in fact active aggressors. If we are not allaying the pain of others, and only see or care about our own interests, then we are directly contributing to the suffering and poverty of our world.

We have it in our power either to increase the hurt inflicted on our world or else to contribute toward its healing transformation. So when will we realize the detrimental effects of wasteful consumerism on our spiritual, social, cultural, and physical environment? When will we understand how religious and racial intolerance simply cannot lead us out of our impasse, and the way they lock us instead in a vicious cycle of hatred and violence? When will we recognize the obvious irrationality of military violence and national conflict, both of which betray a lack of imagination and willpower? Authentic compassion extends to victims of all forms of social injustice.

Let us put the matter more simply. The way we work, the salaries we earn, the houses we construct, the cars we drive, the money we spend, the luxuries we enjoy, the goods we consume, the resources we waste – all of these, we now know, impact directly on our neighbors within our own society, in our neighborhood and more broadly in our world. Our way of living, we now know, either enhances or else endangers the rest of the earth’s inhabitants as well as all future generations.

The issues of free trade, global commerce, and consumer market growth should be of concern to everybody, not just a few people. Unless that is clearly recognized, then there will be a deeper and deepening chasm between the individual and the community, as well as between the rich and the poor. The notion of community involves values that are shared; they transcend national, political, religious, racial or cultural boundaries. It is a plain fact that as soon as respect for the human person – and for all human persons in community – is abandoned as the supreme principle and purpose of our economy, then other negative consequences will follow rapidly. If people are reduced to the status of consumers, then the ability to manipulate people and influence their consumption becomes all-important and what arises is an insatiable form of greed.

That is why economic and social development must always be tempered and underpinned by moral and social values. Whatever happens in the world, we ought to strive to preserve fundamental cultural values that pertain to humanity without, of course, establishing unnecessary barriers to useful economic progress. At the same time, we also ought to be aware that a globalization of talent is only morally justified when accompanied by a global distribution of the benefits that flow from it.

Nonetheless, while the picture may sometimes appear gloomy, the reality should not be presented as pessimistic. In fact, never before in history has there also been such a widespread interest in and concern for the eradication of poverty and the future of our planet. This is precisely where globalization carries the potential for a positive impact and change within society and our world. For, while it may be true that the gap between rich and poor has never seemed greater, the very fact that such inequality is now palpably obvious, thanks to the images and information that flow so freely around the world, gives us a new priority and renewed focus.

Finally, the world’s monotheistic religions also owe it to their common heritage to imitate their forefather, the Patriarch Abraham. Sitting under the shade of the oak trees at Mamre, Abraham received an unexpected visit from three strangers (recorded in the Book of Genesis, chapter 18). He did not consider them a danger or threat. Instead, he spontaneously shared with them both his friendship and food, extending such a generous hospitality that, in the Orthodox Christian tradition, this scene has been interpreted as the image of God’s love. As a result of his selfless hospitality, Abraham was promised the seemingly impossible, namely the multiplication of this seed of love for generations. Is it too much to hope that our willingness to converse and cooperate as people of different and diverse religious convictions might also result in the seemingly impossible coexistence of all humanity in a peaceful world?

Furthermore, in the Orthodox Christian image of this “Hospitality of Abraham,” iconographers traditionally depict the three guests on three sides, allowing an open space on the fourth side of the table. The icon serves as an open invitation to everyone. Will we choose to sit at the table with these strangers? Will we surrender our prejudice and arrogance in order to take our place at the table for the survival of our world and the future of our children? The icon of Abraham’s hospitality is a powerful symbol of the presence of God among us when we welcome and care for others without inhibition or suspicion. It is the ultimate image of human compassion and social justice.

It is our fervent prayer that this series of the newly inaugurated Istanbul World Forum will contribute to the promotion of such compassion and justice.

See his Homily 19,5 on Matthew, in PG 57.280.

Related Stories

The Istanbul World Forum was held under the theme “Justice” on 13-14 October 2012