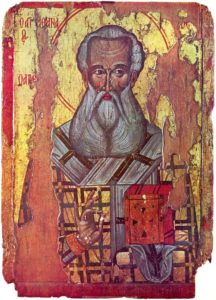

St. Athanasius the Great

Source: Curating Theology

Saint Athanasius’ On the Incarnation (public library) is one of the most significant texts of early Christian theology. It set the terms of the subsequent debates within the church on the nature of Christ and remains to this day one of the foundational texts of theology. Saint Athanasius was the bishop of Alexandria in Egypt, perhaps the most important center of Christianity, during the 4th century. He wrote during a time in which the popular idea of religion remained one where people imagined God needed to be distant from humanity. The gods, many thought, would not debase themselves to involvement in human affairs. This, of course, is at great odds with what Christians have come to believe about the Incarnation—but those settled views were not taken for granted in early Christianity. Athanasius had to actively defend a robust view of the Incarnation from its detractors.

The Apostle Paul wrote centuries earlier of the seeming “folly” of the cross and how difficult it was for people accustomed to a different view of the gods to understand the necessity, in Christian terms, of the Incarnation. Athanasius’ time dealt with these same issues. Although the nature of his arguments and style of argumentation is quite different from how theologians work today, one cannot get around the ingenuity of how Athanasius answered the question: “Why an Incarnation?”Athanasius separates his construction of Christology into two areas: “the Divine Dilemma Regarding Life and Death,” and “the Divine Dilemma Regarding Knowledge and Ignorance.” In this post, I’ll tackle the first issue. In a forthcoming Curating Theology post, I’ll treat the latter point. Let’s get to the basic question. Christians were trying to piece together the varied doctrines of their faith—from the notion of sin to the notion of salvation. How were the two connected? What, indeed, was the problem that Christ’s Incarnation remedied? For Athanasius, part of the problem was that sin caused humans to slip away into non-being and live under the sway of death. Christ, correspondingly, came to bring life!

“Our own cause was the occasion of his descent and our own transgression evoked the Word’s love for human beings, so that the Lord both came to us and appeared among human beings. For we were the purpose of his embodiment, and for our salvation he so loved human beings as to come, be and appear in a human body.”

For Athanasius, human sin cut us off from the grace which we were designed to live amidst. God, as the creator and as supremely good, he argued, could not simply leave creation to perish under its own inertia in the direction of emptiness. That’s an important point to note; humans, in Athanasius’ theological vision, are under the sway of sin—a force so strong that self-willed resistance was futile. Something external to creation, on his view, was absolutely necessary if humans were to escape their fate. But God, being good, and the creator of this creation that was slipping away, wouldn’t let that happen.

“It was therefore right not to permit human beings to be carried away by corruption, because this would be improper to and unworthy of the goodness of God… It was not worthy of the goodness of God that those created by him should be corrupted through deceit… It was supremely improper that the workmanship of God in human beings should disappear either through their own negligence or through the deceit of demons.”

Make no mistake, Athanasius offered a logical argument for the Incarnation. His context is significant here, for the intellectual climate of the first two centuries still believed it totally improper for God to interact so closely with matter; becoming matter (through the Incarnation) was unthinkable! To combat this milieu, Athanasius used philosophical reasoning to portray the Christian theology of the Incarnation in a rational, logical manner. By setting up the drama of redemption that way, Athanasius tried to make it clear that the Incarnation was fitting—further, that it was necessary on account of God’s nature as creator and as good. Astute theologians might wonder whether Athanasius’ theology makes it appear that God is compelled to save humans. Might that minimize the mercy and grace of the Incarnation? That’s a question for another time. However, the short answer, for Athanasius, is that the compulsion here arises not from something external, but from the intrinsic nature of God. In other words, no one is forcing God’s hand here; it’s God’s own love that compels God’s action on our behalf. So, the problem once more: humans have become corrupted by sin. Their natures are marred by the effects of sin. They are spiraling downward. Corruption was an important word for Athanasius. By using it, Athanasius tried to evoke the singular problem presented by sin. It wasn’t merely that humans had wronged God; sin tore deep into their natures.

“Repentance…merely halts sins. If then there were only the offense and not the consequence of corruption, repentance would have been fine.”

Since the problem was not one merely of offense, a change in human nature was required. This is what the Incarnation offered. Here’s how Athanasius describes the effects of the Son taking on a human nature:

“For the Word, realizing that in no other way would the corruption of human beings be undone except, simply, by dying, yet being immortal and the Son of the Father the Word was not able to die, for this reason he takes to himself a body capable of death, in order that it, participating in the Word who is above all, might be sufficient for death on behalf of all, and through the indwelling Word would remain incorruptible, and so corruption might henceforth cease from all by the grace of the resurrection.”

The human nature that the Son assumed was both representative of and connected to human nature more broadly—in such a way that the effects of the divine nature on the human nature spread to all humanity as a result of Christ’s death and resurrection. Read this formulation carefully:

“For being above all, the Word of God consequently, by offering his own temple and his bodily instrument as a substitute for all, fulfilled in death that which was required; and, being with all through the like [body], the incorruptible Son of God consequently clothed all with incorruptibility in the promise concerning the resurrection. And now the very corruption of death no longer holds ground against human beings because of the indwelling Word, in them through the one body.”

Athanasius is a little fuzzy on the mechanism at work here, but we have to remember that this is still very early theology. He’s asking and answering questions for the first time, really. It would take centuries before more substantial language concerning the Incarnation would be formulated in the Church. Nonetheless, Athanasius is clear that the Son’s divine nature was imputed—to an extent—to all humans as the means of their redemption, which overcame the corruption formerly brought about by sin. It’s fascinating to think through the ways one of the most influential Church Fathers tried to think through the reasons of the Incarnation. In response to the “Divine Dilemma Regarding Life and Death,” Athanasius makes a case for the reasonableness of the Incarnation—in spite of its cultural critics—and begins to explain the mechanism of salvation. The development of theology like Athanasius offered precisely follows the Christian maxim, “Faith Seeking Understanding.” Christians always had faith that the Incarnation brought about their redemption. But it was only through questioning, probing, and reflecting that theologians began to offer language to explain that reality. That’s the task of theological reflection that we’re all called to: reflecting on what our faith means for the world. For Athanasius, the Incarnation was God’s necessary method of saving humanity from its ultimate corruption. That’s good news.

Recommended Reading:

- On the Incarnation, Athanasius of Alexandria. I cannot overstate how important this work was for the development of Christian theology. In fact, it’s a good idea for all Christians to read it at some point. The Popular Patristics version linked above is the most readable.

- The Early Church, W.H.C. Frend. Although originally published in 1965, Frend’s survey of early Christian theology remains the gold standard of accessible introductions. Frend traces how theological development followed debates in the life of the Church. It’s indispensable as a go-to secondary text.