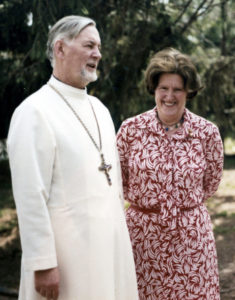

Fr Alexander and Matushka Juliana Schmemann in the early 1970s at St. Vladimir’s Seminary

Source: Orthodoxy in Dialogue

by Serge Schmemann

Monday, January 29, is the first anniversary of the passing of my mother, Juliana Schmemann, in the 94th year of her extraordinary life. To many in the Orthodox Church in America she is known best as the wife of Father Alexander Schmemann, the “L.” (for “Liana”) he so lovingly and so often refers to in his Journals. Many have also read her own remarkable story in two modest books she wrote, My Journey with Father Alexander and The Joy to Serve. On this anniversary, I would like to tell a little more about her life.

My parents were indeed a remarkable couple, drawn to each other from their first meeting, playing opposing roles in a household production of a musical staged in the Paris suburb of Clamart in the winter of 1940-41. He was 19 and she 17. Soon after they met again at the St. Sergius Institute, where my father was a seminarian. He told her he was studying for the priesthood—then slyly added, “but I do not intend to be a monk.”

Father Alexander and Matushka Juliana Schmemann Ordination day, 1946

It may seem self-evident that two such young Russians in Paris would find each other. Yet in that émigré world they came from very different circles. My father came from a family of high-ranking civil servants in St. Petersburg, and through his entire youth attended the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Alexander Nevsky, the heart of the Russian emigration in Paris, where he served as altar boy, reader, and subdeacon, and was ordained priest.

My mother was from an old Russian family, the Ossorguines, who in emigration settled with their vast extended family in the suburb of Clamart, around the tiny family church of SS. Constantine and Helen. The Ossorguines’ great claim to fame was their descent from the 17th-century Saint Juliana of Lazarevo, a wife and mother venerated for her devotion, modesty, and charity in difficult times. The Ossorguines revered St. Juliana, and on one of my mother’s visits while I was a New York Times correspondent in Moscow, we traveled to the ancient city of Murom on the Volga River to venerate the relics of her ancestor and patron saint.

During my time in Moscow, I researched and wrote a book about Russia, Echoes of a Native Land, through the prism of the Ossorguines’ former estate south of Moscow. For my mother’s father and grandfather, their Sergiyevskoye was a spiritual cradle they held dear long after they were forced out by the Russian revolution. Faith was the center of their lives: every member of the family I ever met, including my mother, was intimately familiar with every service and tradition of the Orthodox Church.

My mother was born already outside Russia, in Baden-Baden, Germany, where her mother’s family still owned a villa. They soon moved to Clamart, where my mother’s grandfather, Mikhail Ossorguine, was ordained to the priesthood at age 71 and became the patriarch of the clan. My grandfather, Sergei Ossorguine, was the choir director; the family was the choir. The church, and many relatives, are still there.

When my mother entered an old-age home a few years ago, my wife and I, now living in Paris, would mercilessly grill her about those days. Her memory remained remarkably clear. She recounted how from this tight, patriarchal community she was sent off at age 10 by her doting father to a Catholic boarding school for girls, Sainte-Marie de Neuilly. The school, a pioneer in serious women’s education, played an enormous role in my mother’s development, and she remained a devoted alumna all her life. After Sainte-Marie, she finished a Master’s degree in classics at the Sorbonne.

The French schooling opened her eyes to a world beyond the Russian emigration and its lost world just as my father was undergoing an epiphany of his own. Seeking a broader education, he left the Russian military school to which his parents had sent him and enrolled in a French lycée. He then entered St. Sergius Institute, at that time home to some of Russian Orthodoxy’s greatest theological minds.

They were married on January 23, 1943 at the Cathedral of St. Alexander Nevsky. Photographs show my mother arriving in an elegant horse-and-carriage; that, she explained, was not extravagance but necessity in German-occupied Paris, where fuel was scarce.

In the first years they had marginal income, but that, as my mother recounted, seemed not to matter in those war years. They moved into a log cabin with two rooms and a dirt floor outside Paris and began to raise a family. One of my mother’s proud memories from those years was when a German officer demanded that she cede him her place in a Metro car, as was required during the occupation. When she arose he saw that she was heavily pregnant and was aghast, but she proudly remained standing.

When my father was invited by Father Georges Florovsky to join the faculty of St. Vladimir’s Seminary, they barely hesitated. America beckoned, a new world and a new life, and they were ready. And so in 1951, with three children (Anne, the widow of Father Thomas Hopko; Mary, wife of Father John Tkachuk; and your correspondent), they crossed the Atlantic on the RMS Queen Mary—mother and kids in one cabin, father in another.

One of my mother’s first jobs was as a private French teacher, and I remember how members of an African-American band preparing for a European tour would come to our apartment for lessons. Soon she was a full-time teacher in some of New York’s best girls’ schools.

By all accounts she was a brilliant teacher. I still occasionally meet women in New York who ask whether by any chance I might be the son of Madame Schmemann who taught at Spence, or at Brearley. I was on a jury once, and the judge put that question to me—a Mme. Schmemann had taught his daughter. “That is my mother, your honor,” I replied, “and I presume your daughter is fluent in French.”

In 1977, she was unexpectedly appointed headmistress of the Spence School, a source of great pride to my father and us all. Her guiding idea, which she shared with my father throughout their lives, was the celebration of life. “Joy is an effort, a daily exercise of seeing the beauty of one’s life, through thick and thin; of singing ‘Alleluia!’ on a happy day as well as on one’s dying day … Joy then becomes a habit, an attitude, a state of being,” she said in one interview.

Through their American lives, my parents spent their summers on a lake in the Quebec Laurentians, Lac Labelle, where their relatives and friends, Serge and Lyubov Troubetzkoy, had bought farmland. They built a chapel dedicated to St. Sergius, drawing many more friends and relatives to spend summers there, and for many years my mother, ever the Ossorguine, was the choir director and reader. They loved the place, and we all love it still.

Father Alexander died in 1983. Juliana had supported him and shared his work throughout his ministry, just as he had supported her in her calling. “As I reach the final steps in my journey to the Kingdom,” my mother would write years later, “I look back with endless gratitude for the many years that I spent as a priest’s wife. I am still a priest’s wife.”

Matushka Juliana (seated) in 2013 with her children and their spouses: (L to R) Father Thomas and Matushka Anne Hopko, Father John and Matushka Mary Tkachuk, and Mary and Serge Schmemann

She continued teaching, speaking to parishes and women’s groups, writing, translating Father Alexander’s Journals. In 2003, my mother moved to Montreal to live near my sister, Mary Tkachuk; there, she continued to speak at conferences and seminars until it was time to enter an assisted-living home.

“I look on each day as a blessing,” she wrote in My Journey with Father Alexander. “Each morning I feel lucky to have yet another day to live. At my age, my body is playing up, but I am luckier than many.

“I love living.”

May her memory be eternal.