Source: Public Orthodoxy

by Very Rev. Dr. John Jillions

Visiting Professor at the Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies (Cambridge, UK)

When the New York Times recently asked readers to tell them why they had left their religion behind some 7,000 readers responded (“Why Do People Lose Their Religion?” June 7, 2023). Clearly there is a lot of painful pent-up feeling about this. But an equally intriguing question is, “Why do people keep their religion?” This is a question that percolated throughout a course on religion in American history I was teaching this past Spring at Fordham University (“American Religious Texts and Traditions”).

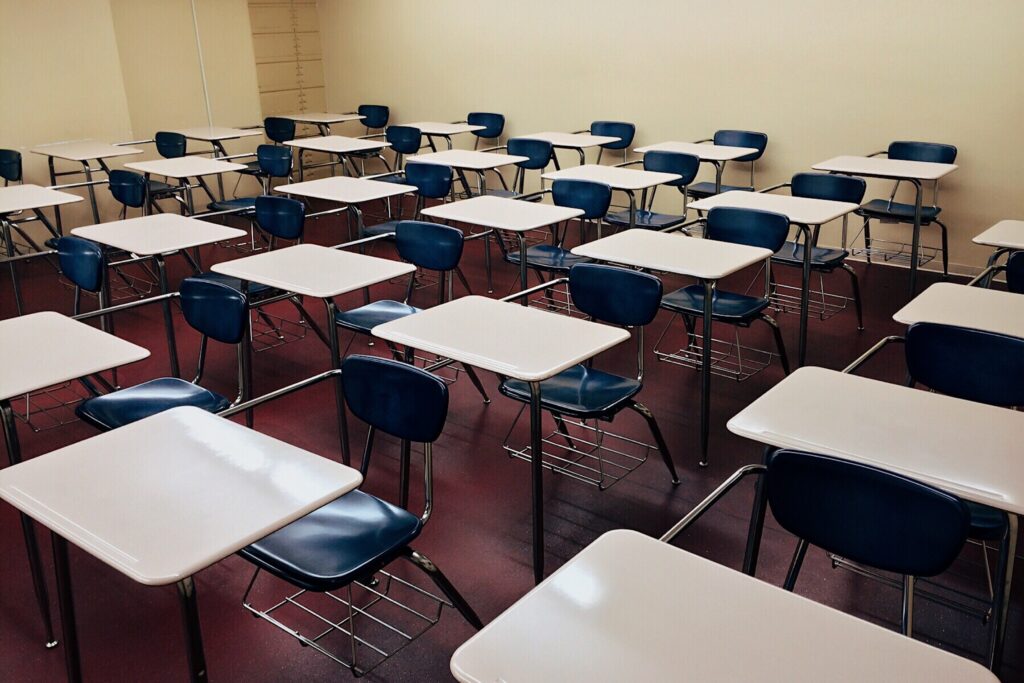

The class of thirty undergraduates at this Catholic institution came from a wide variety of religious backgrounds (and none), and I myself am an Orthodox priest. The academic range in the class was broad and almost evenly divided between sophomores, juniors, and seniors (plus a few freshmen). There wasn’t a theology or religion major among them. They were pursuing English, history, political science, international studies, psychology, visual arts, “humanitarian studies” (how to address disasters, conflicts, poverty, defense of human rights), visual arts, communications, digital technology, biology, psychology, urban studies and—the largest group—business administration, finance, marketing, and accounting.

At the start of the course, I gave them an in-class survey. Their backgrounds were predominantly Christian (Catholic, Episcopalian, Protestant, and one had a Russian Orthodox mother), but also Buddhist, Hindu, Sikh, agnostic, and atheist. 44% said religion was “fairly important” in their life, and an equal 44% said it was “Not very important.” Only 12% said religion was “very important” to them. Few now attend a place of worship (84% said they “rarely” or “never” attend), though as they were growing up 64% had attended with their family at least once a month. A few had been raised without any religious practices. Still, well over half the class (62%) said they pray “often,” “sometimes” or “in times of crisis.” None of this was unexpected. Their move away from institutional religious commitment—while maintaining a sense of spirituality—matches the broad societal trend in the US. But what did surprise me was their capacity to be personally engaged by the history of religion in America and in thinking about America’s religious future.

Early in the course we talked about why religion might be important in peoples’ lives, and the class said that faith could give comfort and community, hope and purpose. It connects people to a tradition, a moral code, and a sense security and inner protection in times of tragedy. But their list of why religion might have lost its importance today was much longer.

- Hypocrisy

- God becomes an escape from taking personal responsibility

- Religion is too associated with extremes

- Community can be found elsewhere

- Tragedies make people question

- There are too many internal religious conflicts and complexities

- Religious tradition can be too constricting

- Beliefs and practices can be outdated and no longer applicable

- Spiritual life is possible without religious membership.

Clearly, the students didn’t have to look very far for reasons to abandon religion. And their survey of religion in American history confirmed many of their suspicions. Much of that e history is associated with intolerance, injustice, and abuse, and no religious groups are free of this taint. Papal decrees and church-backed colonial laws permitted the suppression and enslavement of native peoples and Africans. Puritan divines presided over witch trials in New England and hounded dissenters. Churches of most denominations collaborated with slavery and racial oppression, if given the chance. Religious innovators and immigrants who brought their own forms of religious practice were inevitably ostracized and persecuted by the mainstream majority. Catholics, Quakers, Mormons, Christian Scientists, Jews, Buddhists, Sikhs, Muslims, Hindus—and Orthodox Christians too—have all have gone through this often-violent American hazing process. But once accepted, religious groups on all sides of the political spectrum have organized to lobby for their favored policies to shape local, state, and national government, exercising their constitutional rights to the free exercise of religion and freedom of speech.

The students were alarmed by the eagerness of religious groups to use political power to shape public opinion, even if this meant trampling on the common good and the rights of minorities.

But this is not a new issue. Thomas Jefferson worried that his vision of the separation of church and state could be lost through the power of religious public opinion. Writing in 1818 to the prominent Jewish leader Mordecai M. Noah, Jefferson admitted that “more remains to be done, for although we are free by the law, we are not so in practice. Public opinion erects itself into an inquisition and exercises its office with as much fanaticism as fans the flames of an Auto-da-fé.”

Most shamefully, Christian public opinion gave aid and comfort to slavery. Frederick Douglass excoriated this in the appendix to his 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of an American Slave.

[Between] the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference—so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked. To be the friend of the one, is of necessity to be the enemy of the other. I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land. Indeed, I can see no reason, but the most deceitful one, for calling the religion of this land Christianity.

But the students were also perplexed by the tenacity of faith in the lives of people like Frederick Douglass himself. He knew very well the dignity, power, and purpose that “the Christianity of Christ” gave to so many of the enslaved, and since the age of 22 he had been a licensed preacher of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. If students were troubled by much of America’s religious history, they were also confounded by a host of people in American history who resisted popular religious opinion while keeping faith with the God of their experience—Anne Hutchinson, Roger Williams, William Penn, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day, Daniel Berrigan and many others. Religious faith had been a deep and inexplicable source of personal strength, social justice, community service, engagement, and belonging. The students were also impressed by the spectacular diversity of American religious expressions and their mutual influence over time. And despite its institutional flaws, they saw Christianity—as the majority faith—acquiring an increasingly universal character in its 400-year history, with new forms and constant adaptation but the same core faith in Christ.

On the last day of class I asked for their advice. “What would you want religious leaders to consider for the future of religion in America?”

- Accept diversity; create a welcoming and inclusive environment

- Create opportunities for interfaith dialogue and collaboration, especially on social and environmental issues

- Actively promote social justice and combat inequality

- Recognize the spread of non-denominational churches since people are less tied to a specific religious institution

- Accept the that traditions can adapt to changing social norms without losing their center: “it’s not all or nothing”

- Embrace new technologies

- Encourage questions and intellectual curiosity

- Beware of religious leadership’s entrenched self-interest in preserving the status quo instead of taking action to advance the good of people and the community

As one student said, “They should encourage their members to ask questions, seek knowledge, and engage in meaningful discussions about faith, morality, and ethics. By doing so, religious leaders can create a vibrant and relevant religious community that meets the needs of its members and contributes positively to society.”

Valuable advice as religious leaders wring their hands about declining attendance. Like most teachers I’ll never know the long-term effects of this class on the students’ academic pursuits, careers, and personal lives. But I felt privileged to be let into their thinking on a subject that means a lot to me. And if I planted a question about the facile dismissal of religious faith, then I count that a win.

ABOUT AUTHOR

Very Rev. Dr. John Jillions