Source: Public Orthodoxy

Very Rev. Barouyr Shernezian

Dean of Armenian Theological Seminary of the Catholicosate of the Holy See of Cilicia

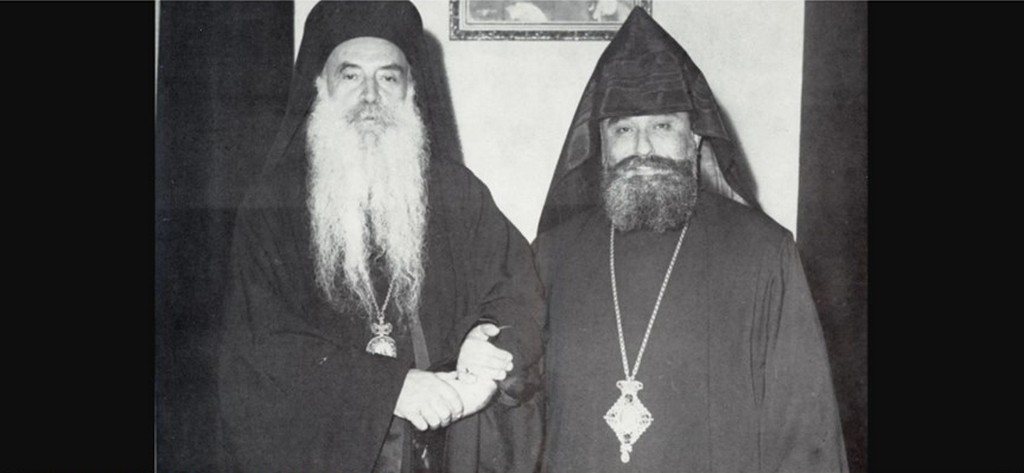

His Holiness Zareh I Catholicos Payasilian of the Armenian Catholicosate of the Holy See of Cilicia (R) and His Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras (L)

Historical imagery has always fascinated me for the significant value it holds for research and inquiry. In my research attempts to explore photographs depicting historical moments, I came across the December 1959 edition of the official magazine of the Armenian Catholicosate of the Holy See of Cilicia, “Hasg,” through which a striking photograph of two spiritual leaders—His Holiness Zareh I Catholicos Payasilian of the Armenian Catholicosate of the Holy See of Cilicia and His Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras, united in a gesture of solidarity, holding hands—caught my attention. Patriarch Athenagoras had embarked on a pontifical visit to the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. In this context, the encounter he had with Zareh I was centered on discussions about the relationship between Christian churches, echoing the unity emphasized in a recent speech by Pope John XXIII.

Undoubtedly, Patriarch Athenagoras held a prominent position in the ecumenical world, making his visits to the Orthodox patriarchates of the East a logical step in fostering intra-Orthodox relationships and unity. However, the broader context, as elucidated by Paschalis M. Kitromilides in his book “Religion and Politics in The Orthodox World,” sheds light on the underlying motivations behind Patriarch Athenagoras’ visits. These visits aimed to safeguard the Middle Eastern Orthodox Churches from Soviet political influence, which had been growing since the 1940s through the Church of Russia. Kitromilides explains, “The political objective of the ecclesiastical primacy sought by Moscow was also transparent: support for Soviet foreign policy through declarations favoring world peace and condemnation of alleged imperialistic plans at the expense of global populations.”[1] After a prolonged period of insularity, the Russian Church, under the encouragement of the Soviet government, sought to reestablish connections with the outside world, both within intra-Orthodox and ecumenical relationships. Paul B. Anderson’s analysis highlights the following: “Yet no one can doubt that Stalin had well in mind the fact that Russia under the tsars had considered herself the Protector of Christians living under the yoke of the Sultan, and that it was advantageous for the Soviet Union at least to intimate a continuance of this policy.”[2] Stalin’s strategic interest in aligning the Russian Church with historical policies of protecting Christians under Ottoman rule was an advantageous position for the Soviet Union.

Following Patriarch Alexei of the Church of Russia’s election, the patriarchate’s activities, especially in the Middle East, gained visibility, raising concerns for opposing entities, including the Ecumenical Patriarchate, symbolically patronizing the remaining Orthodox patriarchates. The meeting between patriarchs Athenagoras and Alexei on Christmas day in 1960 aimed to alleviate tensions stemming from the Cold War remnants. For the Ecumenical Patriarchate, securing the Middle Eastern Orthodox churches from Soviet influence became imperative, elucidating the significance of Patriarch Athenagoras’ historic visit.

The Soviet policy significantly impacted the Armenian Orthodox Church, notably the Armenian Church of Echmiadzin, especially concerning dioceses outside the Soviet Union. Pressure was exerted to keep perceived threats beyond the Union’s borders. Similarly, in 1956, for the first in Armenian Church history, the Catholicos of Echmiadzin, Vazgen I, visited Lebanon, amid to the new election of the Catholicos in the Holy See of Cilicia. This brought enormous tension in the Armenian Church, and many people looked at it as a battle in the nation between the leftists and the right wings; however, this was the impact of the Cold War between the USSR and the West. Tsolin Nalbantian, analyzing the incidents of 1959, describes the election of Zareh I Catholicos as neither a local issue, nor an inner-Church conflict. Still, in the wider context, it is clear it was another battlefield of the Cold War: “The involvement of authorities from a variety of nation-states demonstrated that this election was not merely an Armenian affair. Rather, the 1956 election of the Catholicos of the Cilician See became an international contest to establish authority.”[3] The Armenian Church of Echmiadzin was highly and directly controlled by the Soviet Union. Zareh I Catholicos, who ascended to the throne of the Catholicosate of Cilicia amid challenging circumstances, understood Soviet foreign policy through the lens of his people’s experiences. He discerned how Soviet propaganda influenced Orthodox churches governed under the “Red Flag.” The meeting between the two church leaders, Patriarch Athenagoras and Zareh I Catholicos, thus presented an opportunity for an exchange of experiences in safeguarding the Church in the Middle East from communist influences.

Reflecting on this historic meeting between Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras and Zareh I Catholicos of the Holy See of Cilicia, one cannot help but contemplate the challenges facing the Orthodox Church today and the imperative for unity, transcending mere dialogues. Geopolitical issues strain relationships between churches, creating tensions rather than fostering cohesion. The significance of interconnected gas pipelines and trade routes often overshadows the fundamental principles of Christ’s love and the mission entrusted to us. Now, more than ever, the interconnection and relationship between Christian churches, especially within the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Church, are indispensable. Patriarch Athenagoras’ words resoundingly remind us: “Let the dogmas be placed in the storeroom… the age of Dogma has passed.”[4] It is time to reaffirm our commitment to the Word of God and His true Body. Amid countless reasons for divergence, the love of Christ stands as the unifying force. Aram I Catholicos encapsulates the Church’s mission: “The raison d’être of the church includes two inseparable dimensions: unity in Christ and service to humanity.”[5] These dimensions should galvanize our collective efforts, uniting our strengths to build a resilient Church, rooted deeply and branching out in myriad ways. Such a tree would weather any storm or adversity, standing unwaveringly in its conviction.

[1] Paschalis M. Kitromilides, “Religion and Politics in The Orthodox World: The Ecumenical Patriarchate and The Challenges of Modernity,” (London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2019), 85-86.

[2] Paul B. Anderson, “The Orthodox Church in Soviet Russia,” Foreign Affairs 39, no. 2 (January 1961): 306, https://doi.org/10.2307/20029488.

[3] Tsolin Nalbantian, “Articulating Power Through The Parochial: The 1956 Armenian Church Election in Lebanon,” Mashriq & Mahjar 1, no. 2 (46-79): 60, ISSN 2169-4435.

[4] Patriarch Athenagoras expressed these words in The Holy Land, during his historical meeting with Pope Paul VI in 1963. Constantine Cavarnos, “Ecumenism Examined: A Concise Analytical Discussion of the Contemporary Ecumenical Movement,” (Institute for Byzantine & Modern Greek Studies, 1997), 11, 28-30.

[5] Aram I Catholicos Keshishian, “Orthodox Perspectives On Mission,” (Catholicosate of Holy See of Cilicia: Antelias, 1996), 97.