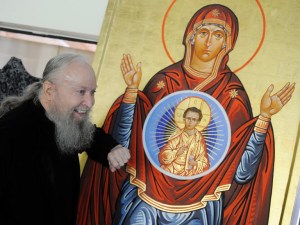

Orthodox icons of the birth of Jesus are not like those in Catholic and Protestant churches. “We do not focus on a magic baby in Bethlehem,” says B.C. Archbishop Lazar Puhalo. Here Jesus is portrayed as a youth of about 12. Orthodox don’t believe in “atonement” theology.

Source: The Vancouver Sun

by Douglas Todd

Orthodox Archbishop Lazar Puhalo is four days away from completing his annual 40-day Nativity fast.

He refrains from meat, eggs, dairy products, anger, envy and other questionable habits during this time to “discipline the soul.”

The 73-year-old leader of an Orthodox monastery in a remote corner of the Fraser Valley says of self-denial: “It is an attempt to control what usually controls us.”

The hierarch’s fast will end on Christmas Eve – as it does for hundreds of millions of Orthodox Christians around the world.

Orthodox Christians prefer to refer to that which people in the West know as “Christmas” as “The Nativity of Christ,” the birth of Jesus. And many of Puhalo’s thousands of followers join him in calling the mystical birthdate something even more holy: “The incarnation of God on Earth.”

The Nativity of Christ, says Puhalo, marks the spiritual “upheaval of the universe.”

No more. No less. The Orthodox celebration of the birth of Jesus is far from the secular Western Christmas customs involving Santa Claus, non-stop shopping, cheery tunes about White Christmases and sparkling ornaments on evergreen trees.

The Nativity of Christ is not a time for “entertainment,” says the archbishop, whose monastery is called All Saints of North America.

Instead Puhalo sees the Nativity of Christ as a “very solemn day.” It marks the embodiment of God on Earth, the day God became flesh in Jesus, and, potentially, in all creatures.

Orthodox Nativity services are replete with incense, confession of wrongdoing, revering of icons, reciting of the Psalms and up to three hours of standing, since in Orthodox churches it is not customary to sit in pews.

The archbishop believes the Nativity of Christ is as important for salvation as Easter (which marks Jesus’s death and resurrection). So he says, with a smile, that the many hundreds of Metro Vancouver adherents who attend his seasonal services “do not complain about standing up.”

Asked if Orthodox church members might enter into an altered-state-of-consciousness while repeating the many rituals surrounding Nativity of Christ services, Puhalo responds: “I hope they do.”

DIFFERENT DAYS OBSERVED

Orthodox Christians make up the third-largest branch of Christianity, after Roman Catholics and Protestants.

To people in the West, one of the best-known Orthodox Christians may be the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky, author of Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov.

Throughout the world there are an estimated 250 million Orthodox Christians (who are often called Eastern Orthodox). There are many of them in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Romania, Georgia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and Balkan countries such as Croatia and Serbia. There are about 500,000 in Canada, with 60,000 in B.C.

It is hard for many in the West to keep track of the hundreds of streams within Orthodoxy, which are often shaped by national customs. And it is understandable many are befuddled about Orthodox Christmas.

One reason is that some of the world’s Orthodox celebrate the birth of Jesus on Dec. 25 (following the Gregorian calendar) while many other Orthodox mark it on Jan. 7 (following the Julian calendar).

The Orthodox archbishop deals with the variance in the date surrounding the Nativity of Christ by leading a series of elaborate services at the monastery and elsewhere in Metro Vancouver on both Dec. 25 (typically for Greeks) and Jan. 7 (typically for Russians and Eastern Europeans).

Although Orthodox Christians are similar to Roman Catholics and Protestants in the way they focus on Jesus Christ as sage, healer and saviour, they are also different, largely because of the Great Schism of 1054.

That’s when Eastern Christians finally rejected the authority of the Roman Catholic popes. They walk their own path, which they consider more traditional.

As a result, Orthodox leaders often appear to Westerners to be exotic. Archbishop Puhalo is an example.

ARCHBISHOP ON YOUTUBE

A brilliant scholar and passionate mystic, Puhalo is often referred to as His Eminence, or Vladika, which he says means “shepherd” in Slavic languages.

He is a hierarch in the denomination known as The Orthodox Church in America. His ethnic roots are in Serbia, but he speaks many languages.

Puhalo lives with a half-dozen monks at a simple, pastoral monastery nestled at the foot of the mountains near the hamlet of Dewdney, about 65 kilometres east of Vancouver. Despite his remote home base, Puhalo frequently travels to give lectures – including recently at Oxford and the University of Pennsylvania.

Though the archbishop can cut an intimidating figure in his large cassocked frame, he has a ready smile, genial demeanour and a quick wit. His long grey beard and hair are unshorn, which he says is meant to convey a lack of vanity.

His black cassock (often worn with a box-shaped mitre) suggests gravitas, but it doesn’t drown out his free spirit. The outfit, as he says, is similar to that which men wore millennia ago in the Middle East.

Fearlessly public and open to technology, Lazar has permitted some admirers to create about 1,000 YouTube videos depicting him speaking on matters biblical, ethical, scientific and metaphysical.

Compared to other Orthodox priests in Canada, many of whom struggle with English or French, Lazar says: “I’m much more outspoken and less afraid.”

He offered his views on the Nativity of Christ, and all sorts of topics, during an extensive interview in his monastery office that looks out on a truck-sized boulder and a thicket, which is often frequented by bears and cougars.

He discussed his most recent catapult into popular culture; an appearance in the noted documentary Hellbound?

B.C filmmaker Kevin Miller’s film, released this fall, provocatively explores the many ways North American Christians believe in hell.

The things Puhalo says about hell in the documentary relate directly to his views on the significance of the Nativity of Christ. In Hellbound?, the archbishop counters the views of many evangelical preachers who claim God is busily dividing humans into those who will rise into heavenly paradise and those who will descend into eternal flames.

In the documentary, Puhalo says hell does not exist in a literal otherworldly sense. Instead, he teaches hell is the fire of malice that we often feel here on Earth.

“Heaven and hell are the same place,” he explains in the interview. “How you experience them depends on your conscience.”

An image of burning hell conveys a terribly false portrayal of the God who has been incarnated in Jesus Christ at the Nativity, he says.

Concepts of eternal torment hand too many Christians a rationale to “hate” others; to believe people who disagree with them are “not really human.” He considers such “total lack of sympathy” to be a form of “evil.”

Instead, Puhalo believes the Nativity of Christ overcomes any need for a literal hell. The Nativity provides all humans with the possibility of divine redemption.

ORIGINAL SIN ‘GOOFY IDEA’

The meaning of the Nativity of Christ to Puhalo is revealed in the lavish Orthodox icons on display throughout the monastery. Many give a prominent role to Mary, mother of Jesus.

The archbishop goes to pains to explain that Orthodox icons of the birth of Jesus are not like those in Catholic and Protestant churches.

They generally do not show Jesus as a “helpless baby,” he says. “We do not focus on a magic baby in Bethlehem.”

Puhalo emphasizes the point by gesturing to one prominent nativity scene.

It shows Mary with her arms upraised, revering a small male youth who seems to be radiating out of her chest. The youth is encapsulated in a circle of rays, an object of praise and wonder. The archbishop says the icon portrays Jesus at age 12, when he was emerging as a teacher, an embodiment of the divine.

Explaining further, Puhalo spells out why the incarnation of God at the Nativity is equal to the Easter story.

Along with other Orthodox theologians, Puhalo opposes the popular Roman Catholic and Protestant position known as atonement theology. He rejects atonement theology‘s teaching that Jesus died on the cross to “atone” for the sins of all humanity – “as a sacrifice to pacify an angry God.”

This idea of “substitutionary sacrifice,” he says, did not rise into prominence until after AD 1000, long after Orthodox Christian leaders had mapped out their own theology of salvation. That’s why Muslims also do not accept it.

Puhalo goes on to add that the conservative Western Christian concept of original sin, that all humans are born inherently corrupt, is a “goofy idea.” Why ignore, he wonders, the essential goodness of men and women? What about compassion? That’s what the Nativity is about.

Puhalo believes one of the most important cosmic messages of both the Nativity and the crucifixion is that we are most human, most like God, when we respond to the suffering of others.

COMBINING TRADITIONAL AND LIBERAL THEOLOGY

Even though Puhalo considers himself a deeply traditional Christian, he is a so-called liberal on many theological and social issues.

He firmly believes in an “old Earth,” for instance. Countering the teachings of Protestant Biblical creationists who believe the world is 6,000 years old, he shows off a large stone fossil found above the monastery. As a student of science, it illustrates to him the Earth is at least 4.5 billion years old.

Lazar also calls himself a “Red Tory,” in part because he’s been active in politics for decades, working in tandem with Ron Dart, a religious studies professor at the University of the Fraser Valley. He is pleased that Prime Minister Stephen Harper, an evangelical Protestant, is not talking about criminalizing abortion, because that would be playing into the hands of the religious right.

The archbishop is also upset with the way some conservative Christians treat gays and lesbians. He has written prayer-poems about several homosexual teenagers who committed suicide after being shamed by their religious families.

In addition, Puhalo says he’s “been a feminist since the early ’60s.” He’s particularly proud of one monastery icon showing three first-century Orthodox female healers/doctors who have come to be known as “The Mothers of Modern Medicine.”

In an era in which Americans still argue over whether to install universal health care, Puhalo boasts about how, during the 1,000 years of the Byzantine Empire, Orthodox leaders ensured medical care was public and available to all.

In no small part the Orthodox archbishop’s views on hot-button social issues have been shaped by his theology about the Nativity – which he says symbolizes the “co-suffering love of God.”

Puhalo doesn’t believe the Orthodox Church should uphold strict dogmatism or over-emphasize moral wrongdoing, especially related to sexuality.

Sin is simply the “misuse” of God’s energy, he says. “The incarnation of God on earth” is not about “moralism,” which he says can be a “substitute for love.”

“The Nativity of Christ is when the God who created the world becomes incarnate,” he says. It is a moment of mystical liberation.

“In the Nativity of Christ, the foundations of the Earth have been shaken.”