Source: Helleniscope

EDITOR’S NOTE (Nick Stamatakis): We received this interesting white paper (Charter Whitepaper) through our sources in the Charter committee. Father Nicholas Metrakos, using his scientific background, analyzes the benefits of a polycentric, decentralized model for the Archdiocese. It is very close to how America is organized and successful as a governing model – decentralization is exactly what makes this country a democracy and so successful at all levels. Father Nicholas Metrakos proposes the movement to a “polycentric matrix” through refinement and not through “correction”…

Polycentrism: A Model Worthy of Refinement Not Reversion

Fr. Nicholas Metrakos, Submitted to the Charter Committee of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, March 2022

Introduction

Unconfirmed reports and an official survey disseminated by the Archdiocese indicate a potential interest in a reversion towards a more centralized governance structure. Insights from secular fields may be applicable to the organization of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese. The organization of the Archdiocese in the 2002 Charter represents a natural evolution that requires further development to improve its effectiveness. The movement of the Archdiocese towards a polycentric matrix is a logical progression representative of collaborative models whose effectiveness has been demonstrated in other organizations – not an aberration in need of correction. Through refinement of the current administrative model the Archdiocese can better serve its clergy and laity.

The Fall of Kabul

When the world watched the Afghani government collapse in 2021 there was a sense of hopelessness and deep sadness: tragic loss of life, desperate attempts to flee impending slaughter, and a general confusion. How was it possible, after so many trillions of dollars and decades of involvement, for the well-supported Afghani to government fail? What went wrong?

Two years before the fall of Kabul, in 2019, Dr. Jennifer Murtazashvili, a political scientist and founding director of the Center for Governance and Markets at the University of Pittsburgh penned an article called Pathologies of Centralized State-Building.1 In this article Dr. Murtazashvili argues that centralization undermines the efforts to stabilize and rebuild fragile states. She points to several modern, failed attempts by foreign states (including Afghanistan) to set-up powerful, centralized governments. Specifically, these centralized governments alienated local elites and undermined the quality of public administration by being largely unresponsive to local demands. As an alternative, she proposes that a polycentric model would have been more effective, a model in which multiple, coexisting centers of power have local autonomy for shared decision making. In this polycentric model she demonstrates that the state can be more responsive to local demands and can improve the efficiency of making public goods available to a populace. In her analysis of the woes affecting Afghanistan, she identifies several important points:

- The central government can receive information more effectively from local authorities to distribute public goods efficiently.

- Central governments tend to view informal practices and differences as impediments to cohesion while in fact these practices may be developed mechanisms for ensuring cohesion.

- Decentralization provides for checks and balances where local authorities can prevent a drift in predatory practices exhibited by the central government.

- Centralized authority and the desire to impose uniform rule in fragmented environments widens the gap between de facto practices and formal regulation.

Her nearly prophetic article certainly helps to better understand the context leading up to the fall of Kabul but perhaps there are lessons from this analysis of Afghanistan that are applicable to the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America.

Matrix Management

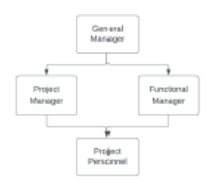

The organizational theory of Matrix Management was first formalized in the late 1970’s and has become the almost universally recognized standard for organizational configuration in the private sector across different industries. In a matrix managed organization, a group or person may report to different groups or people depending upon the nature of the work. For example, a project manager may have oversight for the timing of work product produced by personnel, but the content and quality of the work product is overseen by their functional manager. The basic unit of a matrix organization is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Basic unit of a matrix organization

As expected, matrix management has strengths: it improves collaboration and flexibility, encourages open communication, and increases the capacity to adapt to changing needs; and weaknesses: it can lack clarity around roles and responsibilities, there is the potential for conflict between functional and project managers, and the decision-making process may be slower.

Organizations that benefit most from matrix management are those organizations where there is a high degree of complexity and interrelationship between the activities and projects of the organization. For matrix management to function effectively clear processes (with training) and continuous monitoring of organizational health are critical. The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America is a highly complex organization with many stakeholders and decision-makers working on diverse tasks on multiple levels that has developed naturally into a matrix organization.

The Evolution of Archdiocesan Governance

The creation of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese in the 1920s was intended to bring order, harmony, and unity, to “exercise governing authority over and maintain advisory relations with Greek Orthodox Churches throughout North and South America.”2 This strongly centralized governance structure became more decentralized in 1977 when the Ecumenical Patriarchate granted a new charter that created regional dioceses with a bishop operating under the Archbishop through a synod. This act of decentralization was viewed as an act of “Americanization” to fit the needs of a unique context.3 Negatively, these acts of decentralization, and the increased involvement of laity in ecclesiastical governance, were viewed not just a movement to become more American, but as the result of Protestant influence on the operations of the Greek Orthodox Church.4

The tensions between centralization and decentralization, and the relationship between the Archdiocese and the Ecumenical Patriarchate, reached a public boiling point in 2002 when the events of the Clergy-Laity Congress were featured in the national press. In December 2002, a new charter was granted by the Ecumenical Patriarchate that elevated each diocese and bishop to a metropolis and metropolitan, while “affirming the unity and oneness of the Archdiocese.”5 On the one hand, the 2002 Charter can be viewed as an act of decentralization with respect to the Archdiocese but also as an act of centralization with respect to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, putting regional administrative units directly under the Ecumenical Patriarch. In October 2020, the 2002 Charter was suspended and the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese continues to operate according to the status quo until the issuance of a new charter by the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

The Polycentric Matrix

The Archdiocese is fragile: modern American society has become largely apathetic (if not hostile) to organized religion. There is a persistent murkiness about our own identity vis-Ã -vis Orthodoxy and Hellenism. The effectiveness of centralized administrative processes has been called into question in public ways undermining trust in the Archdiocese. The recent pandemic has exacerbated and highlighted this fragility.

The Archdiocese functions by the will and in reference to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. With respect to ecclesiology, and most importantly, the two bodies are certainly not “foreign†to each other in any way. At the same time, we must acknowledge that administrative and cultural practices between the Phanar and the United States are different and distinct. This is not a weakness but rather a strength of our Ecumenical Patriarchate: in this diversity of practices, customs, and languages we see a living testament to the embracing, nurturing nature of our Mother Church.

While an imperfect model, perhaps the Archdiocese can be likened to a fragile state that benefits from and depends upon the involvement of a “foreign” entity. With this model in mind, Dr. Murtazashvili’s insights about Afghanistan would seem worthy of consideration for our governance:

• Decentralization creates a system of checks and balances to ensure ideas, policies, and desires from the Archdiocese are appropriate to and fit within the local context of each region of the United States.

• Within the Metropolis system, information and requests can be synthesized and presented to the Archdiocese for clear action and leadership.

• Decentralized ecclesiastical governance of regions of the United States allows for a diversity of local practices to provide cohesion without overly uniform practices imposed from above that may be received as alien and unfamiliar.

The Archdiocese has naturally developed into a matrix managed organization where the Archdiocese serves as the project manager and the Ecumenical Patriarchate serves as both the general manager and functional manager (see Figure 2). Like matrix managed organizations, this construct has its strengths and weaknesses, many of which are obvious and do not bear repeating. The solution to the improvement of this system is not a process of reversion but a process of progression. This is a process, where the interactions between “functional” and “project” managers are better defined, it is one of continued advancement and refinement.

Figure 2. Basic unit of the Archdiocese’s matrix organization

Over time the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America has naturally developed from a centralized and linear form of governance to a polycentric and matrix organization as shown in Figure 3. This development is a necessary, evolutionary response to the geographic expanse of the United States and regional differences in culture and politics. This polycentric matrix model creates a greater connection between each metropolis (and its faithful) with the Ecumenical Patriarchate while allowing for national oversight and coordination at the Archdiocesan level. It both affirms our identity as rational sheep in the fold of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and our unity as American Greek Orthodox Christians.

Figure 3. Progression of the organization in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese

Conclusion

It is not clear whether formal analyses using modern organizational theory have been applied to the development of the Charter granted by the Ecumenical Patriarchate to the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. This preliminary analysis is intended to lead to further discussions about the optimization of the current administrative structure of the Archdiocese not its reversion. Like all continuous improvement projects, the process of optimization does not lie within a singular mind, nor can it be carried out hastily as the implications are widespread and complex. Through collaboration, transparency, and reflection across all levels of the Archdiocese we have the opportunity to bring forward the labor of the pioneers of the Archdiocese towards a greater efficiency. As work commences towards a charter to sustain the Greek Orthodox Church for the next 100 years or more, intense, collaborative work is needed to bring forth refined fruits in the vineyard using the tools of the 21st century, rooted in the rich soil of Orthodox tradition, watered by the love of a Mother Church, and illuminated by the Triple Sun of the Holy Trinity.

1 Murtazashvili, Jennifer “Pathologies of Centralized State-Building,” PRISM 8 no. 2 (2019): 54-67.

2 Resolution of General Convention of Canonical Clerics of the Greek Orthodox Church, September 1921.

3 Kitroeff, Alexander. The Greek Orthodox Church in America: A Modern History (Ithaca and London: Northern Illinois University Press, 2020), 246.

4 Kitroeff 345.

5 December 20, 2002, Announcement from the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America (https://www.goarch.org/-/charter-granted-by-ecumenical-patriarchate)

1 Comment

This thoughtful and insightful White Paper developing a plan for improving the governance of the Archdiocese needs your input. The Charter Committee has been working for over 1 year and has not provided us with drafts to consider or ways for us to express our thoughts on how the Archdiocese should be governed. The Committee has had one ZOOM Meeting. Father Nicholas provides us with a plan that we can consider and use to express our vision for the Archdiocese.

The governance of the Archdiocese and Metropolises is the work of all the people and must include opportunities for clergy and laity to be part of the governance process. The charter must restore the input of clergy and laity so that they are not just a rubber stamp for the needs of foreign Patriarchates and governments. The charter should contain provisions to be the bridge for developing a unified and inclusive Orthodox Christian governing body in the USA. It should be the basis of spiritual renewal of the faithful who live in this geographic area.